|

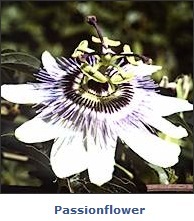

| The passionflower, a close relative of the violets, is a woody-stemmed climbing plant that grows to a height of 10 m (30 ft). Passionflowers are cultivated for their unique flowers and edible fruits. |

Passionflower, common name for a flowering plant family, and especially for members of its principal genus. The flowers are usually perfect, generally having a five-parted calyx and five-parted corolla. All species have a more or less conspicuous crown of filaments springing from the throat of the tube formed by the base of the calyx and corolla. The family contains about 530 species, most of which are climbing plants, such as the passion vine of the southern United States, which sometimes reaches a height of 9 m (30 ft). The bell apple, or water lemon, of the West Indies is a species of passionflower with an edible fruit. The giant granadilla is a closely related plant native to Jamaica and South America. The pulp, or aril, surrounding each seed of the giant granadilla plant is used in flavoring drinks and ices.

Scientific classification: Passionflowers make up the family Passifloraceae. The principal genus is Passiflora. The passion vine is classified as Passiflora incarnata, the bell apple, or water lemon, as Passiflora laurifolia, and the giant granadilla as Passiflora quadrangularis.